The predominant and most widely-used

school of thought in use for the psychotherapy of borderline personality

disorder (BPD) is called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT). Marsha Linehan, a

psychologist at the University of Washington, was the person who came up with

the theory and treatment ideas. The treatment paradigm has been shown in studies to be somewhat

effective in reducing some symptoms of the disorder, but mostly ineffective

in helping patients solve their problems with love and work.

She believes that a combination

of a genetic propensity to be over-reactive combines with a so-called “invalidating

environment” to produce the disorder. Studies that attempt to identify genetic propensities tend to have

a major flaws in distinguishing normal neural plasticity in response to the

environment from purely genetic effects, although the combination of a baby

that tends towards being reactive and a parent with attachment issues would be problematic

– an example of gene-environment interaction rather than just genetics.

The invalidating environment is

clearly that in the patient’s family of origin, although this is seldom spelled

out in the DBT literature.

Interestingly, in 2011.

Linehan, in a story in the New York Times, “…admits that when she was

younger, she "attacked herself habitually, burning her wrists with

cigarettes, slashing her arms, her legs, her midsection, using any sharp object

she could get her hands on." She added, “I felt totally empty, like

the Tin Man." Self injurious behavior and feeling empty are two of

the hallmark symptoms of BPD. Did she have the disorder? According

to the article at least, BPD is a diagnosis "that she would have given her

young self."

So

I was intrigued when she recently published her memoir. I was particularly

interested in hearing about her family of origin and hints of any shared psychodynamic

conflicts they may have had, a phenomenon that she appears to be clueless about with her

patients. I had wondered why, if she came from such a family, she rarely wrote

about how to address invalidating family members, as opposed to merely teaching

patients “radical acceptance” of their parents’ ongoing behavior so they react much

less.

So if she herself had BPD, and if an

invalidating environment is one of two main causes of the disorder as she

theorizes, I've long wondered how come she does not address this very much in

her treatment plan. She says she sometimes does family therapy, but mentions

it only briefly and without any details both in her memoir and her primary book

about DBT.

While

I cannot be certain of anything about her family based just on what she chooses to reveal in her

memoir, the family’s conflicts over gender roles – particularly career

aspirations for women – and religion just seem to jump off the page of her memoir. So the

following forms the basis for my speculations.

She

herself draws the parallel between her mother’s experiences growing up and her own conflicts with her mother. The mother’s parents were described as having lost

their fortune and died young. The mother then took a job to support her two younger

brothers but later moved in with a maternal aunt, who drilled into her head

that she was to be a social butterfly and attract a successful businessman for

a mate. Which she did. Yet she never seemed particularly enamored with her husband.

In

particular, her aunt told her she had to lose weight to be more attractive. She

did that. She never again had a paying job, but was extremely active doing

charity work and also painting. Her art was admired and was hung up prominently

in their house, but Marsha only found out that she was the artist much later. I

guess traditional women could work as long as they didn’t get paid and thereby threaten

their husband’s traditional image. Mom did all this work despite having six young children.

The

author writes that marriage and children were most important for mother as they

generally were for her generation where she grew up. But were they really, or

was she just following her family’s rules?

When

Marsha was a teen Mom tried compulsively to get Marsha to do the same thing her

aunt made her do - unsuccessfully. Marsh was compared negatively with her

younger sister who followed the supposed family philosophy re marriage and

work. In particular, Mom constantly nagged Marsha about losing weight. Marsha

was the only child in the family with a weight problem, so perhaps that wasn’t “genetic.”

Marsha writes that the thing she wanted to do more than anything was to gain

her Mom’s approval, but somehow she couldn’t manage to do this one simple thing - that

her Mother had been able to do - in order to get it.

Marsha

writes clearly that she knew that Mom’s relationship with her great aunt was the

reason her Mom was so critical of her, but she seems to not understand exactly what

made her family act out this issue in the first place nor exactly how it might

be transmitted from a previous generation to her. Again, her solution in DBT

seems to be “radical acceptance” – you just use mindfulness to accept this

reality without trying to change anything, and to stay calm.

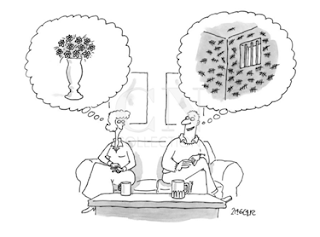

If

she were my patient, I would start to explore the possibility that she actually

was doing what her mother seemed to

need her to do - in effect acting out her mother’s repressed ambition, so clear in her non-family activities – so mother could experience her success

vicariously. And then trying without success to put up with her Mom constantly

invalidating it. Meanwhile, sister Aline was acting out the other side of conflict

and appeared to be Mom’s favorite. Mom even told Aline to stay away from

Marsha. Aline late apologized to Marsha for this but only after Mom had passed

away.

When

it comes to religion, Marsha’s description of her behavior seems even more

conflicted. She was a practicing Roman Catholic throughout her life, and says that

her mother “gave” that to her. However, in the book she frequently criticizes

the church for such things as its rampant sexism and for the belief of the Pope’s infallibility.

She disputes the circular argument heard by many fellow parishioners that God

is real because it says so in the Bible. She later started to mix Catholic ideas

about God with Zen Buddhist ideas about the ultimate oneness of everything in

the universe in ways which are basically incomprehensible.

Further

evidence of conflicts over beliefs and how they may have played into her issues

regarding marriage: she couldn’t marry the guy who she most loved because he

wanted to enter the priesthood. Even though he didn’t and eventually married.

She wouldn’t marry her next boyfriend because he was an atheist. Going from one

extreme to another and ending up in the same place - single - is a hallmark of an intrapsychic conflict.

Mixed messages from parents conflicted over the role of being parents is in my theory the hallmark of families with BPD members, and this one seems to qualify. Her mother having six children and no apparent career might be evidence for such a conflict. Dr. Linehan was hospitalized with self cutting and suicide threats for over two years just weeks

before finishing high school.