Is pornography addiction

a real condition? In the book I co-edited, Groupthink

in Science, we have a chapter by Nicole Prause, a neuroscientist who has

been very active in this debate (and is mentioned prominently in the book I’ll

be talking abut). She makes what I consider an extremely good case that this “addiction”

model is nonsensical. I agree.

In her book, The Pornography Wars, academic

sociologist Dr. Kelsey Burke examines in fine detail both sides of this ongoing

debate without clearly taking a position either way. She talks with a variety

of academics and members of interest and church groups and gets them to open up

considerably about their opinions. Clearly, a lot of the debate is based more

on ideology than on science. On both sides! As we all know, sex is a subject

that has created a huge disturbance in human culture, what with religion,

gender issues, Victorian culture, and the like.

My own view is that sex

negativity is still rampant in the United States, despite the fact that most

people these days engage in relations prior to marriage. They often feel somewhat

guilty about it afterwards. Interestingly, this has put radical feminists and

religious fundamentalists on the same side of the pornography debate. What strange

bedfellows indeed.

Now, to be extra clear,

sex trafficking and being forced to participate in a porn film are issues that

are completely legitimate. No one should be forced to do anything like this

against their will. But in my mind, those issues are very different than the

question of whether pornography per se is bad for anyone, and if so, who and in

what way? Or the question of whether watching it compulsively in maladaptive

ways is a “disease.”

I believe questions about addictions as true mental diseases should be limited to those substances, such

as alcohol and opiates when used to excess, lead to tolerance and serious

withdrawal symptoms. Just about anything can be used to excess and create

negative consequences for the users and their associates. To me, most so-called

“addictions” are nothing more than self-destructive behavior designed to have

certain affects on family relationships and romantic partners.

I’d now like to list a

few examples of the evidence for what I am saying here from the book in

question. Research in this field, the author points out, depends on

self-reports by subjects - which is not objective data, and which are highly

dependent on the types of questions researchers ask and how they are phrased.

There is, for example, a phenomenon called acquiescence,

in which subjects’ responses are likely to go along with the values implied

in the question - for example asking only about negative consequences but avoiding

questions about positive benefits.

Lying about issues with

moral implications is widely prevalent. Does anybody really believe that a female brought up in an

evangelical religion will admit to secretly enjoying watching porn and having experienced

no actual negative consequences from doing so outside of maybe feeling guilty? Additionally, it is obvious that people’s beliefs

about porn influence the consequences they experience during and after watching

it.

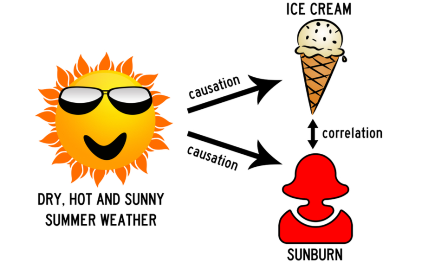

Another issue is

correlation versus causation. Is watching porn bad for marriage, or does a bad

marriage lead to more porn viewing? An interesting finding: Protestant men are

more likely than any other, group, including atheists, to consider themselves

addicted to porn. Yet they report watching less

porn than the other groups. Several studies show that religious commitment is a

better predictor of people believing they

are addicted than actual porn usage.

As I have discussed in

several other posts, the fact that the brain’s connections are plastic and

change all the time when exposed to environmental influences makes claims that

neuroscience has “proved” that a porn “addicted” person has an organic disease

incorrect. As Dr. Burke points out, nature and nurture and their interactions

are what lead to most brains study results. And the boundaries between these

things are “far from tidy.”

Another point: just

because someone has a higher libido than someone else does not mean that they are sex addicts - they

just want sex more often. Also, home porn may often be a cue for some other

reward like masturbation. In a laboratory setting, contingencies like these

aren’t in the cards.

Then there is a prominent Protestant theological teaching. A quote from one of Billy Graham's recently

posthumously-published newspaper columns sums it up concisely. He writes, “All people are sinners in need of a Savior.” What this means is clear

from his sermons: prohibited but universal individualistic desires such as lust

are evidence that we are all evil in the eyes of God and need to renounce

our biological nature and follow what God – really the church – tells us to do.

Or else. In the words of a woman at a church group’s conference on the harms

created by porn addiction, "...after the Garden of Eden we’ve been running from

God ever since.”

This also has led to perceptions about men versus women’s sexuality. Religion teaches us that sin was created by a woman’s curiosity when Eve bit into the apple. In

the middle ages, women were actually considered the lustier of the two sexes

due to the impurity associated with Eve’s curiosity. In the 1800’s during the

industrial revolution and mass migration from family farms into cities, this

changed into its opposite: women changed from Eve to Mary. Women were thought

to want sex, not for itself, but only in order to insure the commitment of

marriage. “Why buy the cow if you can get the milk for free?” was a question

asked by confirmed virgins. Although men were thought to want sex way more than

women, they were also perceived as being less in control of their behavior. Masculinity

was defined as being in control, so if they “conquered” the natural sinfulness

of a porn addiction, this was thought of as an accomplishment.

In my opinion, the function that all this mythology serves is to show

the negative effect of allowing yourself to express lust, so the people who are

doing without get to feel more justified in giving freer sex up. Said one Christian

who had “overcome” a porn “addiction,” quoted in the book, he was “…tired of

not being the person that God made me to be.”

Well, what about those

radical feminists? They are certainly not primarily evangelical Christians.

Nonetheless, they have without realizing it accepted the Christian dogma while

trying to frame it as something else. Both Evangelicals and radical feminists

believe that men feel entitled to sex and women are both objectified and

victimized. The radical feminists seem to implicitly accept the idea that women

cannot want and enjoy sex as much as men, despite the fact that they can have

multiple orgasms and men cannot. The

general sex negativity towards women's lust prevalent in both sexes in our “patriarchal” society was summed up nicely by Elise Loehnen: "Good women want to be seen as sensual, warm and inviting of sex, but not overtly interested."

Because of the prevalence of these gender

attitudes and in order to sell more, porn does in fact frequently show women being objectified

by men. The feminists use this to “prove” their point,

ignoring that this occurs because of the cultural groupthink expectations of the audience. And there are plenty of women who

somehow enjoy watching porn as much as men do even under these circumstances.